Sanctuaries for Captive Cetaceans

Removing the last obstacle to a better life

The Whale Sanctuary Project, a new non-profit organization launched last week, has been met with much enthusiasm and relief by animal advocates, scientists and people everywhere who understand not only that it is impossible for orcas and other marine mammals to thrive in concrete tanks, but that it is fundamentally immoral to use them in this way.

The project is headed by Dr. Naomi Rose, marine mammal scientist for the Animal Welfare Institute; David Phillips, co-founder and executive director of Earth Island Institute and director of the International Marine Mammal Project; and myself.

While the Whale Sanctuary Project is a separate organization from The Kimmela Center, it shares an underlying philosophy in several key ways. First, it is based on best scientific practices and applies the expertise of a stellar list of experts in fields ranging from marine mammal science, veterinary medicine and training, to engineering, to law and policy, and business and management. We will be providing a tangible way to shift our relationship with these animals from one of exploitation to restitution: restoring as much of what we’ve taken from them as we can.

This new project will also offer cutting edge educational and outreach programs to show people who these animals are and why they should live in the oceans rather than in concrete tanks. This can only be done in a setting like a sanctuary where the animals are not being exploited.

Second, The Whale Sanctuary Project is one of an ongoing series of societal improvements in how we treat other animals, particularly those who demonstrate many of the same psychological characteristics as us humans, like vulnerability to the stresses of confinement, boredom and loss of autonomy.

In 2011, for example, the National Institutes of Health decided to end their funding of biomedical research on chimpanzees, and in 2015 announced plans to retire all chimpanzees in government facilities to sanctuaries.

Last week, the University of Louisiana’s New Iberia Research Center announced it would send to the new Project Chimps sanctuary not only Hercules and Leo, two chimpanzees whose freedom the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) has been fighting to secure for more than two years, but also the 218 other chimpanzees who remain in captivity at that facility. I worked as Science Director for the NhRP when they filed a habeas corpus lawsuit against Stony Brook University in April 2015. The organization achieved an unprecedented legal victory for nonhuman animals when New York County Supreme Court Justice Barbara Jaffe issued an Order to Show Cause that required Stony Brook (where Hercules and Leo were being held for research) to come into Court and give a legally sufficient reason for detaining them. Rather than let the case proceed through the legal system, New Iberia chose to take the two chimpanzees back to Louisiana and began negotiations the NhRP and with sanctuaries.

Also last week, and again in response to public demands, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus put on their last elephant show. They are sending all their captive pachyderms to their retirement facility in Florida.

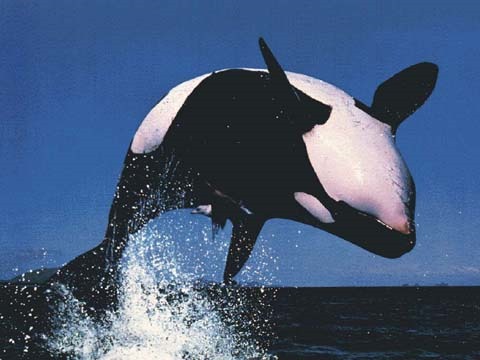

Twenty-five orcas will still be held at theme parks, forced to live out their remaining lives in concrete tanks.Over the last five years, public opinion has also shifted regarding entertainment companies holding dolphins and whales captive in concrete tanks. Following the killing of trainer Dawn Brancheau by orca Tilikum in 2010, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration ordered SeaWorld to end human “water work” with orcas during shows. Since that time, numerous legislative and legal efforts have been initiated to end the captive breeding of orcas and other cetaceans in marine parks and to phase out their use in entertainment. And last month, SeaWorld acceded to public pressure and announced an end to all orca breeding in their parks around the world immediately.

As laudable as this decision was, it doesn’t go far enough. Twenty-five orcas will still be held at theme parks in North America, forced to live out their remaining lives in concrete tanks. While most of them were born in captivity, Tilikum (who is now gravely ill at SeaWorld Orlando), Lolita at Miami Seaquarium, Corky at SeaWorld San Diego, and Kiska at Marineland in Canada were all taken from their families in the wild.

While many organizations and individuals are working to have cetaceans retired from captivity at theme parks, there is one major obstacle to these efforts: there is currently nowhere for them to go. None of them can be released directly into the wild, and most, if not all, will require lifetime care in a sanctuary setting.

The Whale Sanctuary Project is setting out to remove this obstacle. Our mission is to establish a model seaside sanctuary where cetaceans (porpoises, dolphins and whales) can be rehabilitated or can live permanently in an environment that maximizes well-being and autonomy and is as close as possible to their natural habitat. And we invite SeaWorld and other marine parks to join us in the realization of this last phase of shifting our relationship with marine mammals from one of exploitation to one of respect.

The creation of The Whale Sanctuary Project was made possible by a generous initial donation from the socially conscious company Munchkin Inc., makers of innovative products for babies and children, and its CEO, Steven Dunn. They have also pledged at least $1 million toward the completion of the first sanctuary. Through their Project Orca, they have been dedicated advocates for the retirement of orcas and other cetaceans to seaside sanctuaries where they can thrive.

Please visit the website of The Whale Sanctuary Project for more details on how we are moving closer to our goal of creating the first permanent cetacean sanctuary in North America and how you can help support it.