Human/Nonhuman Chimeras: Saving Our Bodies, Losing Our Souls

I’m a neuroscientist and a new paper in the journal Cell has me worried. The paper details the creation of a human/pig chimera by implanting human pluripotent stem cells into a pig embryo.

While the paper describes very preliminary steps towards the development of human/ungulate chimeras, the goal of the research program is to generate pigs and cows with human organs. Since cows and pigs are similar in size to humans, these organs could then be harvested and transplanted into humans as well as used for research on human disease, development and evolution. The key organs targeted in this research are heart, liver, kidney, pancreas, lungs and brains. Pigs and cows would become, essentially, living containers for human organs.

Another expectation of this kind of research is that these chimeras will serve as improved models for testing drug treatments, as well as boosting the availability of tissue for research and providing an unlimited source of organs.

Pigs and cows would become, essentially, living containers for human organs.

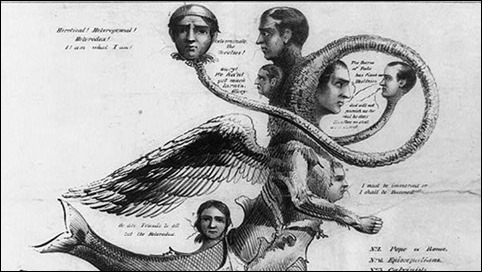

This research is part of a larger trend toward increasingly invasive and manipulative practices, from the domestication of animals for food, thousands of years ago, to the current culture of genetically modifying animals of many kinds: monkeys who show symptoms of autism, transgenic mice with altered vocalizations so that they “stutter”, cows who produce “humanized” milk, and mice injected with human brain cells that cause them to learn faster than normal.

The possibilities have many researchers giddy with excitement. But they also raise serious ethical dilemmas regarding the moral status of these part-human animals. The chimera test subjects have to be human enough to serve as effective models for health research, but not so “substantively humanized” that they qualify for protection from this research altogether.

Certainly, we all want to alleviate human suffering. But the need does not dictate the solution. As we continue down the path of this unprecedented manipulation of sentient beings, we simultaneously limit funding for alternative solutions to our health problems, including prevention, consensual human trials, incentives for organ donation, microchip testing, and in vitro research. All too soon, when we look back on the path of chimeric research that we’ve chosen, we may not like what we see. But it will be too late.

A particular area of concern is the creation of chimeras with human brain cells. These organisms may be capable of self-awareness to the extent that they understand their identity and circumstances, which will produce unbearable suffering. Will we know when the phenomenology of such a being has crossed, what for almost all people would be, the generally-accepted line of decency and morality? If we cannot say with certainty that this will never happen, we need to stop right now before we find ourselves in a world where there is no line.

These concerns about chimeric research do not negate the already potent ethical issues associated with mainstream invasive animal research. Tens of millions of animals are sickened, injured, genetically manipulated and killed in biomedical labs every year. And a robust body of scientific literature has shown that other animals are more self-aware, emotionally and cognitively complex than we previously thought, leading to the inescapable conclusion that we have already crossed a number of moral lines. Chimeric research will only exacerbate the suffering of animals and move it into areas of unforeseen consequences for which we are totally unprepared.

Unless we confront these issues now, we will find that our unrestricted efforts to save our bodies from sickness came at an unwelcome cost: the loss of our souls.